Julian Assange

621 weeks of deprivation of liberty for telling the truth

621 weeks of deprivation of liberty for telling the truth

June 2013, city of Guadalajara, capital of the state of Jalisco in Mexico. An employee of the company Bioparques de Occidente pushes the door of the police premises. His story uncovers a new case of overexploitation of agricultural labor in a large company, a quasi-slavery that still exists all over the world, here and there, especially in areas of intensive agricultural production.

The intervention of the police will make it possible to deliver 275 people retained by this exploitation of production and export of tomatoes. Originally from rural communities in several Mexican states, this workforce was recruited by radio ads promising 100 pesos per day, food and lodging. The reality was quite different according to Valentin Hernandez, one of the surviving employees of this open-air prison. « We arrived a month ago with my wife. They housed us in a room measuring two by four meters, which we shared with two other couples who also have children« he explained.

« The work day is 12 hours and they pay us 70 pesos. The food is rancid and rotten. They tell you that you can leave if you want, but they hide your things and threaten you to stay. And if someone escapes, they catch them, they beat them ».

The salary was in fact made up of vouchers valid in the company’s stores, which of course charged prohibitive prices. The tomatoes were sold mainly to Mexico and the United States.

The information site OpendataJalisco took a closer look at the man who runs Bioparques de Occidente, Eduardo de la Vega Echavarria. An architect by profession, he has been involved in farming for several decades. The production of lettuce, tomatoes in greenhouses and sugar cane (an activity of the Zurcamex family group) has placed it as the fifth largest agricultural entrepreneur in Sinaloa. According to the weekly newspaper Rio Doce de Culiacan, his links with the political world have allowed him to rake in a substantial amount of aid for his companies. Eduardo named one of his tomatoes after his wife, Kaliruy. The company that imports its production to the United States, Kaliruy Produce Inc, is based in Nogales, Arizona. Eduardo is always enterprising: he chose to invest in the production of ethanol from corn. One of the three planned sites has already been completed, but it seems that the dashing patriarch has paid little attention to the legal process, which is currently getting him into trouble following complaints from environmental groups.

The case of Bioparques de Occidente is not the first stain to splash the success story of don Eduardo. At the beginning of 2013, sugarcane workers of the Zucarmex group, one of the largest in Latin America, were already protesting their working and living conditions. For the tomato and sugar king, the fine claimed by the Secretariat of Labor amounted in August 2013 to 8 million 580,700 pesos for the finding of 53 violations involving 1,507 workers. What happens next is not known at this time.

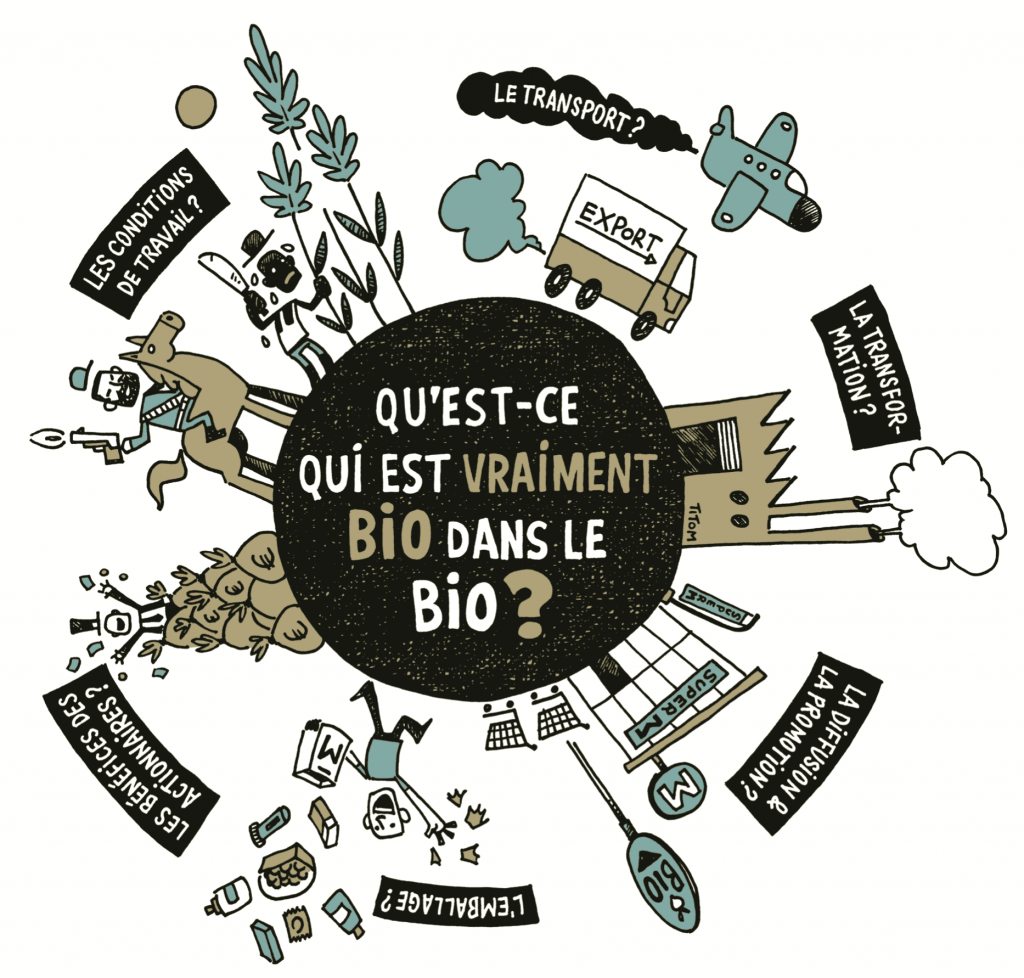

There is one essential information: the tomato produced by Bioparques was organic… For all those who have fought for decades to break with the industrialization of agriculture, the pill is hard to swallow. How can we associate the great social movement that was organic agriculture with what Robert Linhart called « the systematic production of a subaltern humanity, reduced to an almost vegetative existence, but from which capitalism draws a work force »(1)?

Another continent, but similar practices: Morocco has long been seized by the export fever. For the economist Najib Akesbi, it has had only one objective in agriculture since its independence: to export off-season products with high added value thanks to « comparative advantages ».(2) that its climate and geographic proximity to Europe represent. » Agro-exporting development, (…) which has not learned any lesson from the damage of productivism » he says. And it is not the organic agriculture that appeared at the turn of the 90’s that challenged this logic. For the public authorities as for the actors of the sector, it is necessary to support the organic agriculture to answer « the increasing demand of the export markets ». Moreover, according to Najib Akesbi, the Ecocert(3) certification process in Morocco is 99% motivated by access to the international market. In addition to climatic conditions and ease of transportation, Morocco has a third « comparative advantage »: an underpaid workforce. It is the adjustment variable that allows production costs to be lowered and market share to be gained.

In the south of Morocco, in the large Amazigh region of Souss, the province of Chtouka Aït Baha is a mecca for the country’s export-oriented industrial agriculture. On the road leading to Biougra, the greenhouses parade one after the other. At the crossroads, under the advertising signs of the seed companies, women workers, their heads and faces covered with multicolored kerchiefs, hitchhike when they are not crammed into the back of trucks. Along this road is the packaging station of Primeurs Bio du Souss (PBS), the first producer and exporter of fresh organic vegetables in Morocco.

According to Lahcen El Hajjouji, the boss of PBS, everything is going well in the best of worlds. He claims that his workers are paid 15 to 20% more than the legal minimum and that they are represented by a union. The proof: he is being audited by the Business Social Compliance Initiative (BSCI), an offshoot of the European Foreign Trade Association that promotes respect for workers’ rights. But elsewhere, the story is different. Abdelhaq Hissan, local head of the agricultural sector of the Democratic Confederation of Labor, tried to approach PBS workers in 2009. During a social dialogue, local bosses cited the farm as an example. « We then tried to approach the workers of the company, but they did not dare to speak. We think they were afraid. « At the labor inspection, Mr. El Yazidi, delegate of the province of Chtouka Aït Baha, is categorical: at PBS, there is no union. Intended to shed light on this point, the various requests for interviews addressed to Lahcen El Hajjouji have remained unanswered.

According to the FNSA-UMT(4), the country’s largest agricultural union, nearly 100,000 workers are employed on the farms of Souss. This workforce, 75% of whom are women, comes from all regions of the country. Triggered by rural poverty in a country where investors are mainly interested in the coastline, internal migration has reached a threshold of 240,000 people per year according to the United Nations. At the end of the 2000s, during several social conflicts, the workers of Souss denounced their working conditions and the obstacles to union freedom. A social auditor testifies to the social practices of industrial agriculture employers in the Sub-Siege Plain. At the request of large European companies, this person, who wishes to remain anonymous, carries out social controls on behalf of a private organization: « In the farms of Souss, whether they are organic or not, the rule is the non-respect of the minimum wage and the non-declaration to the social security fund. In 2012, following repeated demonstrations by agricultural workers in front of the Ministry of Agriculture, the Moroccan authorities scheduled the alignment of the agricultural minimum wage with that of industry in three years. Recent protests indicate that so far this provision has been ignored.

The men and women who fight against discrimination do not only come from the Souss, a large region that provides food for export while the disconnection from domestic consumption needs is worsening and Morocco is importing more and more. This is a consequence of the country’s entry into the WTO(5), of the free trade agreement with the United States and then with Europe.

Well south of Agadir, Western Sahara has become an area of intensive natural resource exploitation since Morocco occupied the former Spanish colony in 1975. In 1989, King Hassan II launched the first greenhouse project in Tiniguir, near Dakhla, under the aegis of the Royal Domains, which later became the Agricultural Domains. It is a subsidiary of SIGER, the all-powerful holding company that belongs to Mohamed VI and is also present in sectors as varied as banking, insurance, mining, real estate, telephony, energy and automobile distribution.

The agricultural choices of the Moroccan government have not been contradicted since then. Tiniguir 2, then Tiniguir 3 were born, supported by the new agricultural reform of 2008, called the Green Morocco Plan, a reform led by the American firm McKinsey. The model remains the large-scale operation, with priority given to private investment and the search for high productivity. Morocco persists in the path of a two-speed agriculture and the development of organic agriculture is part of this logic. Because Tiniguir 3 produces organic vegetables for export… under a Moroccan label through the intermediary of SOPROFEL(6), in order to avoid any dispute over their origin from a territory of Western Sahara.

Hamid Fatmi comes from a poor peasant family in the Middle Atlas. He arrived in Dakhla in 2007. Like all his colleagues, Hamid Fatmi worked indifferently in organic and conventional greenhouses. Very quickly, the formation of a union office became necessary. « We have heard that the union is what gives you rights. » The Tiniguir workers began by demanding better living conditions. The three farms of Tiniguir are located two hours drive from the city of Dakhla, and the workers, all from the so-called « interior » of Morocco, are housed there. They live six to a room of 12 m² where they sleep and cook. The water they drink is the one, loaded with sulfur, which is used to irrigate the crops. « We had to negotiate for several weeks to get drinking water tanks, » recalls Hamid Fatmi, who remembers seeing several of his colleagues suffer from kidney disease. In spite of their demands, they did not obtain any improvement in their housing or the implementation of sanitary relief. After gaining some vacation rights and improving their social security coverage, they will also eventually receive pay slips and a work card. The result was not long in coming, 150 employees were dismissed, they did not demand the application of labor laws in the king’s greenhouses, even if they were in organic production.

Further north, the production of argan oil, the flagship product of Moroccan organic agriculture, mobilizes another workforce, mainly female and from the douars of the rural world. Exclusively family-owned for centuries, it is an essential resource for the two million people living in the territory of the argan grove, which extends from the region of Safi in the north to the edge of the Sahara in the south. The argan oil remains however unknown outside Morocco until the turn of the 90s. An international promotion of the product, driven by Moroccan academics, will then propel this oil on the world market and ensure a rapid rise. But with what consequences for these Berber women who will most often become employees of production cooperatives or private companies?

Since the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, the time has come for « sustainable development ». According to the Brundtland Report (1987), it must not compromise the ability of future generations to meet their needs. Aid programs are beginning to rain down on the argan grove: the SMAP program, which stems from the Euro-Mediterranean partnership for the preservation of biodiversity; the Argan Project, which aims at sustainable socio-economic development; the Moroccan government’s National Human Development Initiative, whose main objective is to reduce poverty; and the international program called « Earth Guest », which stems from a sponsorship action by the Accor hotel chain. They are underpinned by the idea that people preserve a resource and an ecosystem the more they benefit from it. In addition to the preservation of the argan tree, it is to improve the living and working conditions of Berber women. They formed their first cooperative in 1996, followed by dozens of others. The leaflets praise » women in action for a rising oil « , an oil for food or cosmetic use. But organic certification and labeling are essential to access the international market. Ecocert ensures the former, and Normacert ensures compliance with the PGI specifications.

What happens to the cooperators in all this? After having mastered all the phases of production, did they not become simple pickers of argan nuts and crushers to extract the kernels? Can they now afford a liter of oil? A large part of the argan oil for cosmetic use (unroasted kernels) is exported in bulk. The reputation of « elixir of youth » of this oil rich in vitamin E has interested very quickly the big brands. But, as in any export-oriented industry, most of the added value is recovered downstream, as a large part of the oil is exported in bulk. Organic certification has fitted seamlessly into this economic logic. According to Bruno Romagny, an economist and researcher at the IRD, the goals set twenty years ago are far from being achieved: « with the development of the argan industry, rural households have been gradually dispossessed of a heritage asset, which has become a simple commercial luxury product, out of their reach when the oil must be purchased outside family circles.(7). In the name of traceability, sustainable development and the fate of rural populations. And for the benefit of the development strategy of the certification bodies. The reference to the biological is thus perfectly integrated into what B. Romagny and his colleagues consider to be « a very good example of political, economic and symbolic domination of a rural world that still lives in another logic, by what can be called « the world of development »(8).

Whether in Colombia with palm oil, in Bolivia with quinoa, in Mexico with tomatoes, in Morocco with argan oil, isn’t the construction of certified export industries the matrix of the dispossession of local populations, the exploitation of the workforce and the predation of natural resources, starting with water? To ensure the priority needs of the populations or to bring in foreign currency for the exporting intermediaries and the State? Organic agriculture will not escape this question, unless it is definitively confined to technical specifications and a marketing tool. In 2013, Ecocert created an « eco-sustainable golf » standard. Perhaps the organization will certify golf courses created on argan tree clearings in the Essaouira region after having certified the argan oil of this region? When there were still trees…

Patrick Herman

Farmer in the south Aveyron since the 80’s, independent journalist, author of La conspiration des instants, ed. Transit Montpellier , 2012, and of the bio, between business and project of society, Ibid.